The Plot Against You

SEVERANCE & the work that’s truly “mysterious & important”

Emergency lights flash red, alarm wailing.

It’s only a matter of time before they come for you and the person you love.

The two of you navigate a maze of nondescript corridors, outrunning fate. No plan yet. Just the instinct to survive… To stay whole… To be together for as long as you can.

[Spoiler alert] Without revealing too much, this is more or less where the second season of Severance leaves us. The finale recalls the last moments of Mike Nichol’s iconic film The Graduate, in which an unlikely couple flees into an uncertain future.

Where will they go? What will they do next?

Severance might be the best TV series I’ve seen in the past decade. Its puzzle box of a story follows Mark Scout, who - like his colleagues - underwent a medical procedure that effectively split him in two. Mark’s “Outie” leads his personal life outside of Lumon Industries, the shadowy corporation that conducts the procedure.

Meanwhile, Mark’s “Innie” leads his work life inside the windowless confines of the Macrodata Refinement department on Lumon’s closely guarded severed floor.

Neither Mark knows much about the other - until they find a way to communicate in the season two finale. Outie Mark realizes that Innie Mark is his own person, with wants and needs that don’t necessarily align with his own.

They are, in effect, two individuals sharing one body.

The finale wouldn’t leave me alone. It followed me into life’s quiet moments… Brushing my teeth, taking a walk, waiting for my coffee to bloom. It’s science fiction, sure, but on some level, Severance illustrates what many of us are doing to ourselves already.

We don’t even need a medical procedure.

Products of efficiency

Culturally, the workplace has taught us how to “split” ourselves to survive, leaving parts of us at the door (or if you’re a Lumon employee, the elevator). In fact, a recent survey suggests that more than a third of workers would opt for real-life severance, if it meant they didn’t have to carry their work lives home with them.

One third.

Let that sink in.

“People who work in a corporate environment - or an environment where they’re part of a greater whole - they are often encouraged to diminish their humanity,” observes Dan Erickson, the show’s creator. “Come in, and only bring the parts of yourself that are going to be valuable here.”

So we do, incentivized by steady paychecks, the possibility of status, and vague assurances from on high that the work is “mysterious and important”, in Severance parlance. “Those of us who can’t feel like we’re being productive, we end up feeling like we’re useless. And we take that to heart.”

It’s an environment that can deprive us of agency, personality, and meaning, since the story it encourages us to tell ourselves about ourselves is that we’re primarily products of efficiency. Pushed too far, it’s a story that warps our perception of our own worth - especially in America.

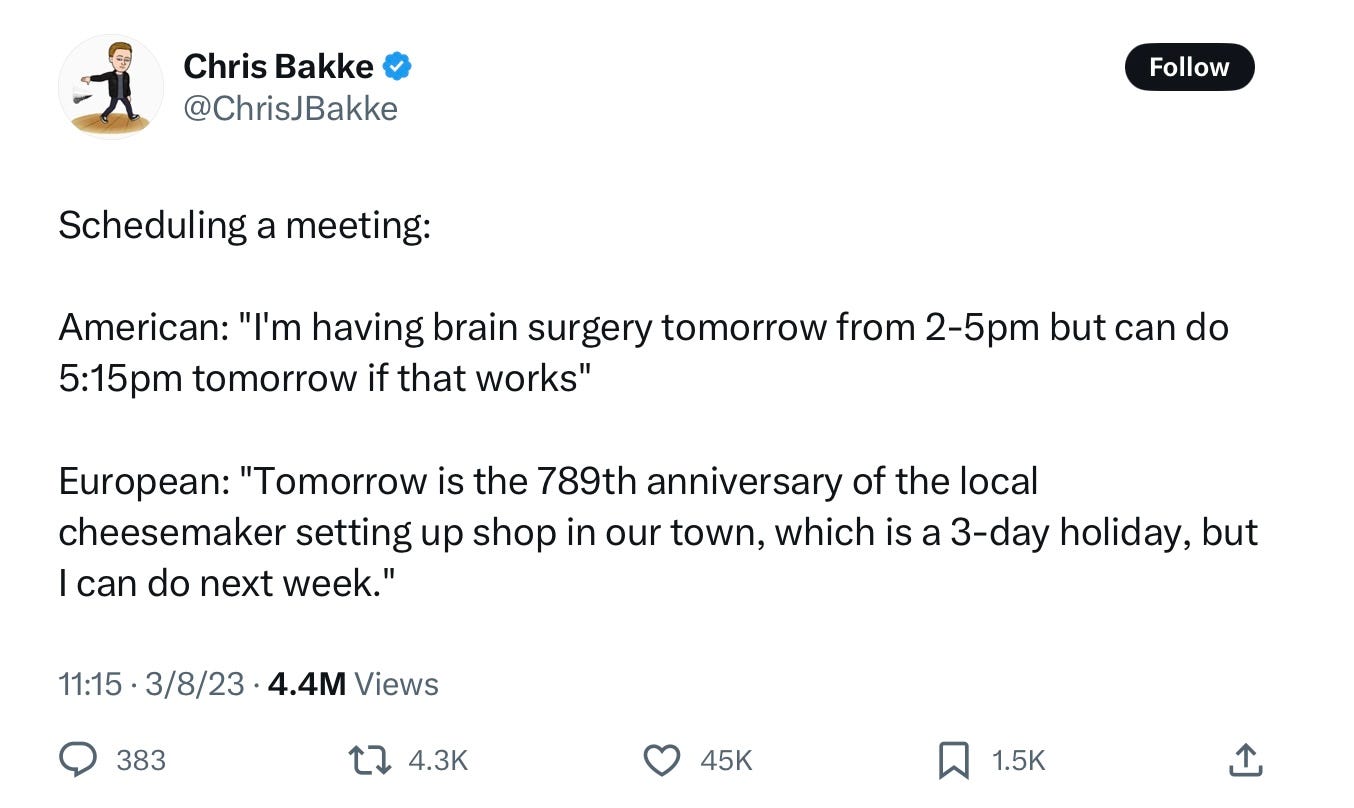

I’ve lived on both sides of The Atlantic - in a small Dutch town, the self-proclaimed “cheese capital of the world” - and I have to say, this hits the nail on the head:

Broadly speaking, Europeans seem to have more balanced relationships with their work than many of their American counterparts. It was one of the few sources of tension between me and my Dutch girlfriend of many years.

In retrospect, I’m grateful for her perspective. It helped me step back and question the outsized influence of work in my life, which was especially confronting as a writer and solopreneur groomed by the competitive spirit of Hollywood and hustle culture.

Sometimes you just want to nurse a good book and beer on a terrace in the sun.

Nobody gets to their deathbed thinking “Damn, I wish I’d worked more.”

The pandemic inspired people around the globe to start thinking along similar lines.

What if it’s possible to live more fully and do your job at the same time?

What if there’s another way that doesn’t necessitate making a deal with the devil?

Rebellion is brewing - in Camus’ words, “born of the spectacle of irrationality, confronted with an unjust and incomprehensible condition.”

More and more of us are “becoming less optimized”, like Severance’s Mark:

[He’s] less willing to understand himself as a product of efficiency… Less willing to contort himself, less willing to sacrifice the stuff of life to a productive scheme that teaches us to understand ourselves as workers at all times.

So freelancing and self-employment are on the rise in modern life, which (for all of their unique frustrations) tend to return a sense of agency to the worker.

Where the 9-to-5 comes from (& where it went wrong)

Historically, there’s precedent for systemic change at the corporate level, too.

During the Industrial Revolution, grueling 16-hour workdays were common. Reformers like Robert Owen pushed for more humane conditions, rallying around the slogan:

“Eight hours’ labour, Eight hours’ recreation, Eight hours’ rest.”

A century later, Henry Ford famously adopted the five-day, 40-hour workweek in 1926, believing it would lead to greater wellbeing, productivity, and profit.

It did.

The Ford Motor Company flourished, and other companies followed suit.

The 9-to-5 model remains the standard today.

Except it’s not just 9-to-5 anymore, is it?

41% of people surveyed struggle to “switch off” after work.

40% have been contacted by their employer after hours.

And 44% routinely check work emails and messages at home.

To be clear, we’re not talking about freelancers and the self-employed, here, who might choose to blur the lines in order to protect their agency, willfulness, and determination. These numbers reflect the experiences of people employed by Lumon and their ilk, in more traditional workplace settings.

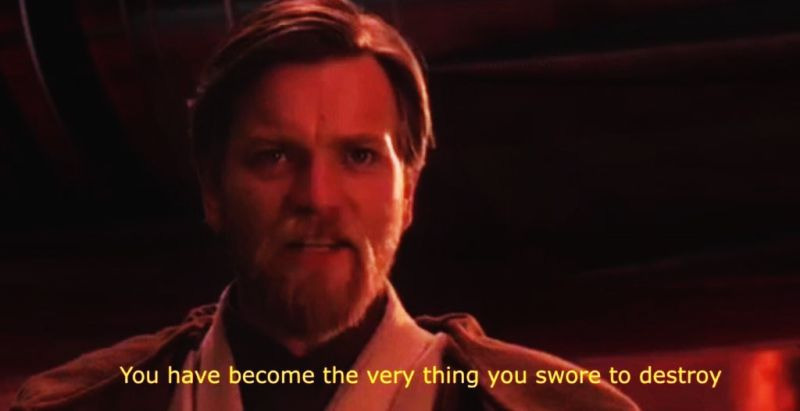

I’m struck by the irony.

The 9-to-5 model was meant to course correct for the Industrial Revolution. It meaningfully improved workers’ lives while maximizing productivity and profit, aligning humanist imperatives with capitalist ones.

But for many, it’s become a prison, trading factory floors for office cubicles.

My mother rejoined the workforce so that she could help her kids get through college in America. For ten years, she spent her daylight hours in a windowless room on someone else’s schedule refining words, much like Mark and his colleagues refining data in Severance. That’s a decade of her life she’ll never get back.

It served its purpose, but again - there must be a better way.

The system should help prevent burnout, not cause it.

The way appears

Two years after the introduction of the 40-hour workweek and one year before The Great Depression, economist John Maynard Keynes imagined what the world would look like in a century. He predicted that by 2028, “the standard of life” in Europe and the US “would be so improved that no one would need to worry about making money.”

Our grandchildren, he wrote, would labor roughly three hours a day - and even that would be more than necessary. The future, it seemed, promised a 15-hour workweek.

Keynes welcomed this age of abundance, but with a warning.

With so little need for labor, people would have to figure out what to do with themselves: “For the first time since his creation, man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem - how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won.”

It’s 2025, and we’re working harder than ever.

Obviously, Keynes’ vision for the future hasn’t materialized - yet.

But the more I work with Artificial Intelligence (more on that another time), the more I realize that in all likelihood, unfathomably unprecedented change is coming.

“Electricity, petrol, steel, rubber, cotton, the chemical industries, automatic machinery and the methods of mass production” convinced Keynes that evolution was inevitable. Perhaps the missing piece of the technological puzzle was AI.

Sam Altman, head of OpenAI, recently shared “three observations”.

Love him or hate him, Altman’s post is worth reading in its entirety.

He argues that AGI - “a system that can tackle increasingly complex problems, at human level, in many fields” - is “another tool in this ever-taller scaffolding of human progress”, but “this time it’s different… The impacts on society will be significant”:

We will find new things to do, new ways to be useful to each other, and new ways to compete, but they may not look very much like the jobs of today.

Agency, willfulness, and determination will likely be extremely valuable… Figuring out how to navigate an ever-changing world will have huge value; resilience and adaptability will be helpful skills to cultivate.

AGI will be the biggest lever ever on human willfulness, and enable individual people to have more impact than ever before, not less.

Keynes asked how we’ll use our time in a world of abundance.

Altman is asking how we’ll express ourselves in a world where technology can do almost everything - except choose a direction.

Which is why it comes back to us, as the emergency lights flash red, alarm wailing.

Sooner or later, they’ll come for you and the person you love.

The two of you navigate a maze of nondescript corridors, outrunning fate. No plan yet. Just the instinct to survive… To stay whole… To be together for as long as you can.

Where will you go? What will you do next?

Lumon & Co. may be threatened, but they’re still in charge.

“In a world that often discourages you… it’s hard to accept all parts of yourself,“ Erickson reflects. “It’s easier to just be one thing. But then that also lessens you and makes you more susceptible to being used by these powerful entities.”

Look, the future has yet to arrive. I recognize that stepping outside the system in some way - even for a season - often depends on things like logistical flexibility and the understanding of family and friends. I’ve been fortunate to have some of that, and I don’t take it for granted. Carving out time to reflect on your life path while also trying to survive it implies a kind of freedom that isn’t always easy to come by.

But if you can, start there. Make some space and give it some thought.

Maybe this can help: The Search for the Ninth Path.

The alternative is to risk getting swept into a future you didn’t choose, molded by values that aren’t your own. As my dad is fond of saying, “Decide what you want your life to look like, or someone else will decide for you.”

You don’t have to have it figured out all at once. Trust the process. Rumi did:

“As you start to walk on the way, the way appears.”

[Spoiler alert] In Severance, before things completely fly off the rails, Mark begins the process of “reintegration”, aiming to collapse his “Outie” and “Innie” identities back into the same experience. It’s a dangerous and painful procedure - which is apt, metaphorically speaking. “Accepting all parts of yourself” can feel like swimming upstream through whitewater, with a hungry grizzly watching from the bank.

You might not get eaten, but the journey will still kick your ass.

Depending on what you need in order to feel whole, it could mean walking away from a steady paycheck, forfeiting your status, and having no superiors around to assure you that the work you’re doing is “mysterious and important”.

To the contrary, if you’re anything like me, some days you’ll wonder if what you’re pursuing is deluded and pointless. You’ll pine for a Lumon fruit platter.

It can be uncomfortable, to say the least. The temptation described by Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor is very real: “In the end they will lay their freedom at our feet, and say to us, ‘Make us your slaves, but feed us.’” Perhaps the scariest part of freedom is realizing you’ll have to choose for yourself what to do, and who to become.

Not an anchor but a mast

In Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, a man who’s spent years living in the distant city of Orphalese prepares to board a ship that will take him across the sea. Before he goes, the people ask him to share some parting words of wisdom.

At one point, a mason asks him about the nature of home.

The prophet replies:

Tell me, people of Orphalese, what have you in these houses?

…Have you peace, the quiet urge that reveals your power? …Have you beauty, that leads the heart from things fashioned of wood and stone to the holy mountain?

…Or have you only comfort, and the lust for comfort, that stealthy thing that enters the house a guest, and then becomes a host, and then a master?

Ay, and it becomes a tamer, and with hook and scourge makes puppets of your larger desires.

Though its hands are silken, its heart is of iron.

It lulls you to sleep only to stand by your bed and jeer at the dignity of the flesh.

…Verily the lust for comfort murders the passion of the soul, and then walks grinning in the funeral.

Mark underwent Lumon’s medical procedure in Severance to avoid feeling the grief of losing his wife. His Outie is effectively “lulled to sleep” for a third of the day - a comparatively comfortable place to be - until he realizes what it actually costs him to allow “hook and scourge” to control him. And as soon as he does?

Rebellion.

Have you murdered your soul’s passion?

Quieted a part of yourself to be accepted, get paid, or keep up with the Joneses?

If you’re “severed” in some way, what is it costing you?

“You restless in rest, you shall not be trapped nor tamed,” the prophet concludes. “Your house shall be not an anchor but a mast.”

Perhaps the real work - the kind that’s truly “mysterious and important” - involves plotting a course that’s consistent with who you are when you’re fully integrated… Fully grounded in yourself as your own sort of “home”.

That sounds like a worthwhile voyage to me.

If you’re navigating a creative pivot and want a focused 1:1 conversation, I offer free storytelling consults. We talk projects, direction, & how to shape your next chapter.