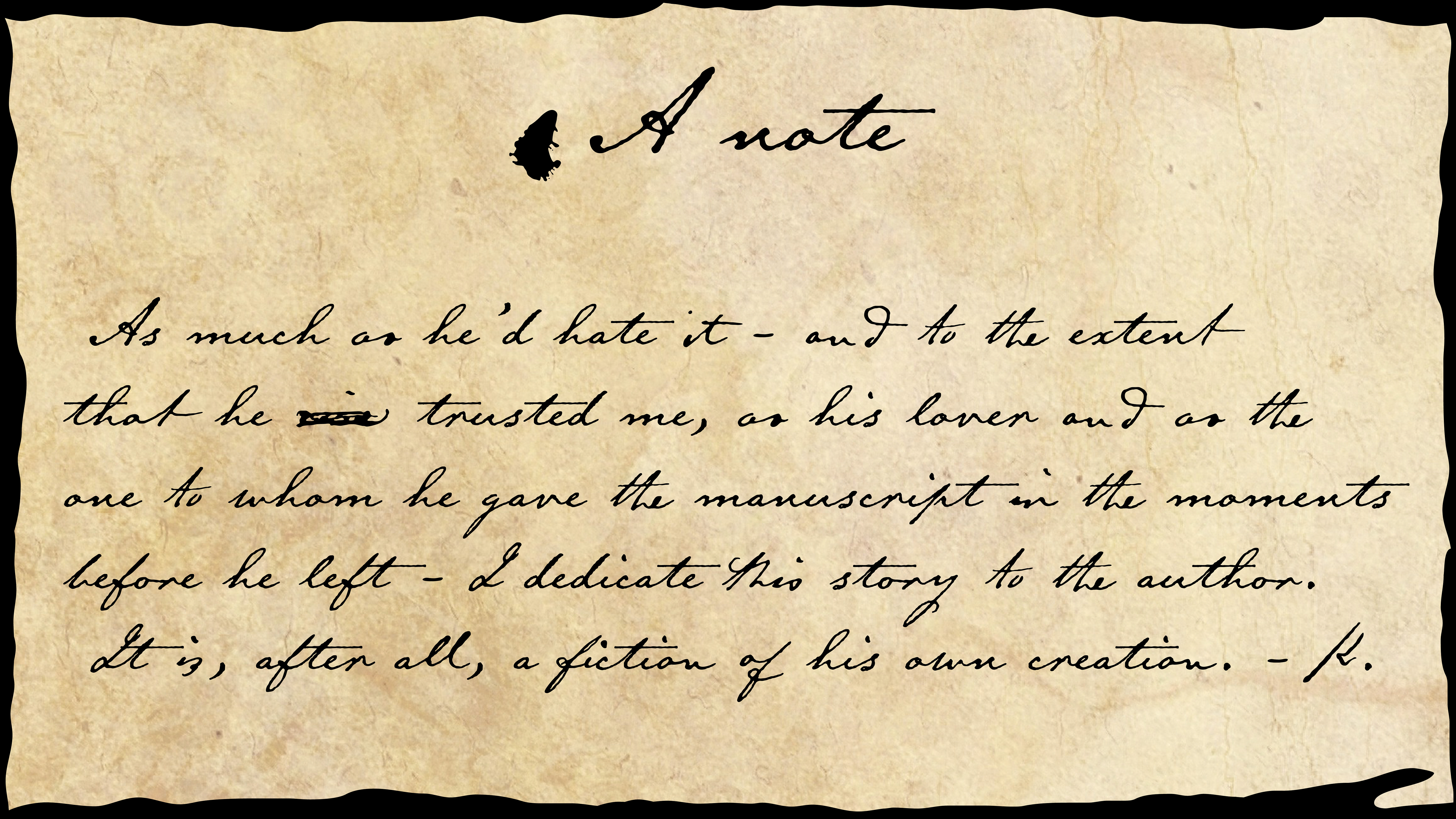

“A fiction of his own creation”

HOUSE OF SNOW: PART II - When a single, fleeting moment alters the course of a life.

Please know

I did not intend for things to turn out this way.

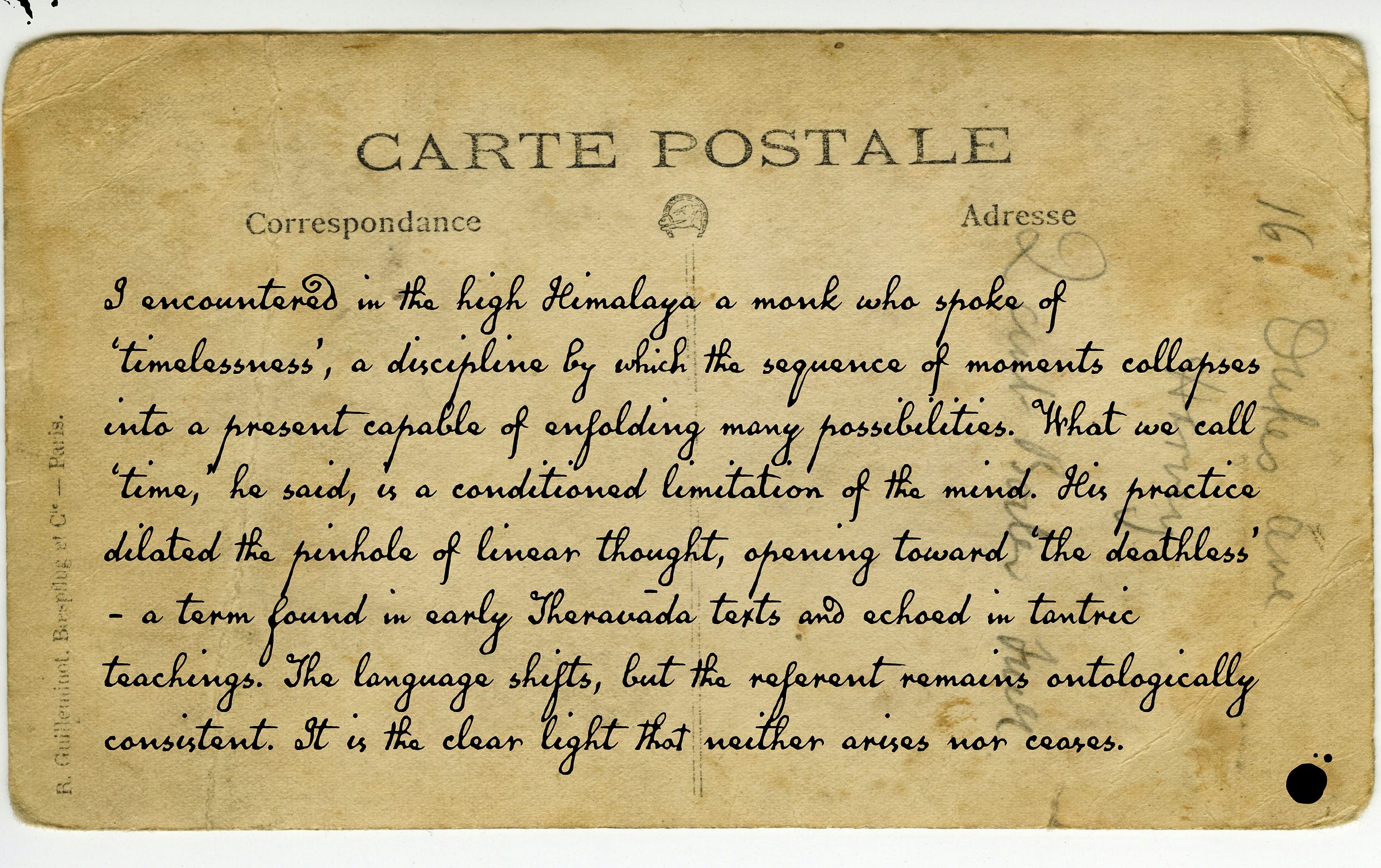

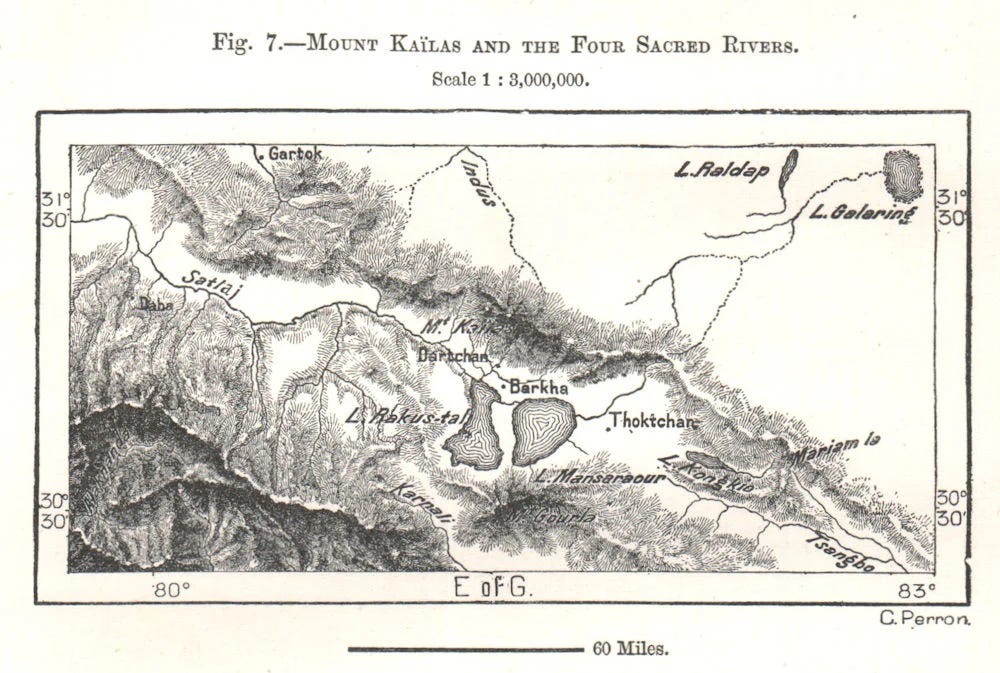

When I found the journals in the antique store where the air smelled of cardamom and burned dust, beneath the portrait of the man with blue skin combing his lover’s hair, I could not have imagined that they would lead to these words, penned on the back of a yellowing survey chart showing approaches toward the Tibetan Plateau.

This is the story of a lost expedition. It’s the story of two people who met in the Himalaya in the mid twentieth century, and who vanished into the snows amidst a doomed guerrilla war. And, I suppose, it’s the story of my disappearance, too.

What can I say, other than that I regret nothing?

I’m watching the mountains burn in the last light of day here. It’s so beautiful. So beautiful. Soon the moon will rise behind them into a purpling dusk, and I will go.

I’ve left you as much as I could.

I hope it is enough.

➡️ Did you miss Part I (the introduction) to HOUSE OF SNOW?

If so, start here:

No vestige of a beginning

Sometimes, just beyond Long Beach where the sun pours into the Andaman Sea, the horizon flashes green. If you see it, you’ll wonder if it’s an illusion, or perhaps the emerald glow of a fisherman’s boat hunting squid in the early dark.

At least, I did, all those years ago. But she laughed and stretched like a cat in the sand and explained that the atmosphere was a prism, bending the light as it vanished.

The first thing I noticed when she appeared in front of me, apparition-like - two rows of bamboo desks down, near the garden - was how the world moved around her. I struggle to put words to it… They bounce off the memory now the same way the light fell off her shoulders then, scattering. But I’ll try.

When I was a kid, I used to think the roads of East Africa sped past us as we sat stationary in my dad’s banged-up Toyota:

Cows, chickens, marabou storks - taxis and motorbikes and Kampala’s multitudes - all of them flowed around us, like water around a rock. Reality bent to my imagination until I grew up and learned about combustion engines.

Kasia must have missed that lesson.

Or more likely, she chose to ignore it since it didn’t apply.

I had just committed to life on the road, and Thailand was the beginning.

My first two visits to the Land of Smiles had been spent deep in the jungled mountains, in a much different context - long story; if you stick around, maybe we’ll get to it - so I was keen for a taste of the island life I’d heard so much about.

The jingle of keys, the sputter of 150cc, lurching down a ribbon of road through lonely fishing villages and between a procession of palms, around a bend in the cliffs that opened into a sweep of blue, pure blue, a cloudlessness melting into the sea. It was an impossible color. Freedom and possibility. Sweat glistened on my arms and stung my eyes, and I welcomed it along with the choking dust. There was the crash of the surf beneath the scream of my motorbike, spewing the fumes of a shitty petrol-whisky blend. My innards rattled as Koh Lanta flowed around me, all liquid frontier.

How can I explain it to you?

How can I make you understand?

As nearly as I could tell, she was between projects. The details were hazy at the time, but I recall something about a non-profit, no money, and real-world psychohistory - Asimov’s idea that the futures of large populations could be predicted by combining history, sociology, and mathematics. So, too, could the developmental trajectories of countries, Kasia said. With enough data, you could game out the implications of proposed policies. It wasn’t perfect, but nothing ever was.

She had just survived a moonless night alone stranded on an estuary in Costa Rica surrounded by crocodiles as the tide rose, so she shared my desire for a taste of the peaceful island life.

I can still hear it… The music of her voice touched by Eastern Europe, woven with the whisper of the palms.

The time she climbed Kilimanjaro, fell sick, got robbed by her guides and hitchhiked across Tanzania. The time I crossed three mountains with no water under cover of nightfall to avoid spies in the deep jungle.

We swapped stories over drinks at Lym’s as the sun went down.

Both of us saw the green flash that night.

Only one of us understood the magic was science.

Which one is multiverse theory, magic or science?

Does one preclude the other?

I’ve been thinking about this a lot, considering all that’s happened since Kasia and I first met.

Multiverse theory builds on established frameworks - cosmic inflation, quantum mechanics, string theory - but as far as we know, it can’t be tested empirically. Still, the sciences circle, attempting to circumscribe it with their proofs.

Edmund understood the tension. At the University of Edinburgh, he followed in the footsteps of giants like James Hutton, quite literally. “The Father of Modern Geology”, Hutton proposed that the planet was vastly older than the few thousand years implied by Biblical chronology… Perhaps geological processes were cyclical and ongoing:

“No vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end.”

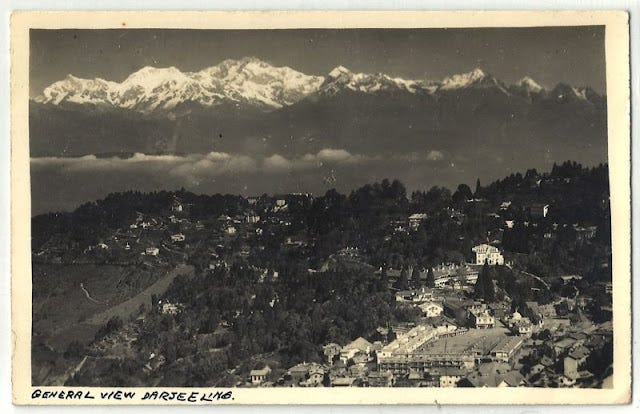

In this particular configuration of this particular universe, Edmund and Samantha crossed paths in Darjeeling, in late 1950, just after the monsoon.

He was twenty-eight and newly unemployed. She was thirty, fresh off an exploratory aid trip to Nepal. Edmund’s journal mentions the Planter’s Club, a fading colonial outpost in the wake of post-Partition India.

I did the research and found that it’s still there today. The original twenty-one rooms have been expanded to thirty-seven. A pair of oxygen cylinders from George Mallory’s fateful Everest expedition flanks the entrance, now more than a century old.

Kanchenjungha looms overhead, long assumed to be the highest mountain in the world. Its name means “the five treasures of the high snow”, which the Lhopo people believe will reveal themselves to the devout when the world is in peril.

The Kanchenjungha of today is the same as in Edmund’s and Samantha’s time. It soars eight thousand meters skyward, high above the Victorian-era architecture of Darjeeling, like an exclamation mark waiting to finish our species’ sentence.

We can’t know exactly what their first encounter was like. But we can infer from Edmund’s journals, the historical context, and supplementary materials I’ve tracked down. Honestly, I’ve lost countless hours to the black hole of archival research since their story first possessed me what feels like a lifetime ago. Scribbled notes on dinner napkins, nights spent crawling the stacks, sifting and synthesizing fragments of a vanished world… You get the idea. More on all of that later.

For now, I hope you’ll forgive me for indulging a reconstruction of Edmund’s and Samantha’s first meeting. It’s the only way I know how to do their story justice.

So brew yourself a cup of coffee and settle in.

Journey with me to the Darjeeling of 1950… A gateway for Himalayan expeditions, its slopes spotted with sprawling tea estates, fast becoming a relic of the Raj.

The wrong lifetime

The main lounge of the Planter’s Club looks like it’s spent years aging inside a whisky glass.

Tobacco smoke stains wood-paneled walls. Sepia photographs hang there like stubborn memories of no one. Leather armchairs recline on Oriental rugs, and shaded lamps pool green on a handful of billiards tables.

The men, predominately white, chalk their cues, read their newspapers, and nurse their imported booze.

Collared shirts, loosened ties, tweed jackets shiny at the elbows, all of the chums aware of Samantha in her simple button-down blouse, leaning easily against the bar.

She can feel their eyes on her. Animals.

Her gaze wanders again to the man sitting alone on the verandah, in khakis and a field jacket, absently fingering a whisky glass beneath a ceiling fan stirring the air. He watches the mountains as if they might speak at any moment.

It’s possible, Samantha thinks to herself, as she nods in thanks for her gin and closes the space between them.

“You look lost,” she says to the man.

She watches his eyes find their way back to the present moment, meeting her own.

“Hm? No, I… Am quite familiar with this place.”

“That’s not what I meant.”

She gestures to the open chair across from him. Curious, Edmund waves his hand in invitation, and Samantha settles in, sensing the mountains behind her.

Billiards balls crack in the lounge, and the men laugh, congratulating themselves. “I’ve seen you around the past couple of days,” she ventures. “Always in this same spot.”

He nods, almond eyes catching the late afternoon light. “You can feel the breeze coming down from Kanchenjungha,” he says.

“Better than the cigar smoke in there.”

He smiles and extends his hand. “Edmund.”

“I know,” she says, shaking it. “The bartender told me about the Teesta Valley Road. Apparently you’re quite the legend.”

Edmund sighs. “I told Kiran no more stories.”

“Hard to stop the one about the ex-soldier geologist who’d rather drink with Nepalis than his own countrymen. Who spent forty-eight hours directing recovery efforts after three days of rain washed away the hillside. That was reckless, you know.”

“Those men would’ve died.”

“You misunderstand. I’m not criticizing you. I’m impressed by the fact that you did anything at all.”

CRACK. More laughter, as Edmund shifts uncomfortably. “What brings you here?”

“I grew up here. Well, Kalimpong, but close enough.”

“So this is home.”

She considers. “Yes. No. I don’t know. We’d come to Darjeeling for supplies and father’s church conferences.”

“Missionaries?”

Samantha shrugs and sips her gin. “Not my world.”

“What, you don’t fancy a game of billiards?”

“No more than you do.”

An understanding passes between them. “Ex-soldier, hm? I’ve known a few.”

“American?”, he prods.

“Is it that obvious?”

“No.”

Samantha waits.

“It’s your energy,” Edmund admits. “Big. Loud, I… Ought to hold my tongue.”

“I’ll try not to be offended. British soldiers, actually. Indian, too. I was with the Friends Ambulance Unit for a long time. Calcutta, Dimapur, around. They kept the religion out of it.”

Edmund blinks. “Dimapur? Really? When?”

“Japanese offensive back in forty-four. The whole corridor was collapsing. We were in crisis mode, Allied troops coming through, refugee camps for all of the displaced workers. It was complete chaos. I was in over my head on that one.”

Edmund blinks and leans back, balancing his chair on two legs. Studying her.

“So Kohima,” he offers.

“Kohima.”

“Could be we’ve met already.”

A breeze floats through the verandah. “It rather feels that way,” Samantha says.

The ceiling fan whirs. “It was another life, but in forty-four, I was, uh. With the Fourteenth Army. Royal Engineers. They redeployed us through Bengal to Dimapur, then north, so…” He trails off. Goes somewhere far away.

“You… You mean you were there? For the fighting.”

CRACK.

Edmund flinches as billiard balls break in the lounge. “The, uh. The tennis court.”

He searches the mountains for answers but finds none.

Silence.

“I want you to come for cocktails at the bungalow tomorrow.”

Edmund drifts back to her. “The bungalow?”

“Friend of mine’s organizing a gathering. I hate these things, but you never know who you’ll meet.”

“No, no, no. I’m no good at all of that.”

She leans forward. “Please? Oh, save me from the bore of it.”

They hold each other’s eyes until Edmund resigns. “You Americans are impossible.”

“Seven. Meet here. I know where to find you.”

She stands and kicks back the rest of her gin.

“Wait. What’s your name?”

Samantha looks down at him. “Seven, hm? I’ll tell you tomorrow.”

Are we the authors of our choices? Is every event the result of prior causes, a chain linking back to the moment of the Big Bang? Or do our decisions emerge from an interdependent web of conditions arising together?

When you plant a seed, the health of the sprout is determined by soil, water, sunlight, temperature. Changes to these conditions affect the outcome. If the future arises from countless conditions - new influences, new intentions, new circumstances, all perpetually in flux - then it’s open, too complex to collapse into a straight line.

Perhaps our choices condition which universe we inhabit.

What strikes me is how a single moment - fleeting, unornamented, a footnote - can alter the trajectory of a life, perhaps because the moment is underpinned by so vast a web of prior causes and conditions. It wasn’t the iceberg above the surface that sunk the Titanic. It was the one hundred thousand year-old behemoth beneath.

One hundred thousand year-old behemoth

I remember the night of the full moon.

There was a party on a far-flung beach you had to know about to get to. Past the open stretch of land with scattered palms pasted in the dark, down the dirt road strewn with boulders, away from where I’d met the witches who’d asked me to dance around their maypole. The parking lot was a tangle of motorbikes when I arrived.

From there, all you had to do was follow the music.

Mushroom Bar looked like someone had uprooted a bamboo forest - shaken, twisted, and skewered it - then transplanted the surviving tangle to the beach, where it laughed and danced like a cartoon man with spindly limbs taunting the rising tide.

The moon pulled the ocean up the shore into the rickety venue, and the sands drank it up.

Already, people were surrendering to the primal beat of the drum thumping out of the festival speakers. Tourists, expats, nomads, beers in-hand, cigarettes, wind curling hair and smoke. Body paint, neon blues and greens and yellows, smeared on legs and arms and faces. Burning like fireflies in the falling night. The building, too, glowed and grinned wickedly.

I was glad to see the charmer from South Africa who traveled carry-on only and the girl with the backwards baseball cap.

“Do you want one?”, she asked, tapping her plastic cup full of brown slush. “You should go get one.” She seized my hands, twirled herself, and disappeared into the gyrating heave of flesh. I never saw her again.

Inspired, I pushed my way to the bar, where a thirteen-year-old kid in an oversized jersey was mixing drinks. He looked up at me with a hungry gleam in his eye. “You want shake?”

I did. For science!

With my very own plastic cup of brown slush, I made my way back to where my friend from South Africa stood on the periphery and took a meaty gulp... It was earthy, thick, sickly sweet.

“I heard they’re grown in elephant shit, bru,” he said. “The mushrooms. When in Rome!”

We drained our drinks together.

At first, nothing. And then - in a single moment, like someone flipping a switch - I felt my body shift into a constant state of ascension. I was flying through the music, I could see the music, each note a kaleidoscope of color, my vision a rainbow.

I staggered through the heat of sweating bodies to the men’s room. The toilet was brimming with piss. I fell to my knees, clutched the bowl, and vomited pineapple fried rice and elephant shit.

“You alright, mate?”, came a voice from nowhere.

“Fine,” I lied, as fireworks dropped the beat and crackled magnificently in front of my eyes.

Out and down, to a bamboo platform in front of the dance floor overlooking the ocean. I clung to it like a life raft. The tide rose, insistent, suggestive, offering to drown me in its depths, gently. I fell through a fever dream of fractals.

My South African friend was there. How long had he been there? And the Swedish girl leaning in, studying me. “I don’t like you,” she said to my friend, fishing a cigarette from his pocket. “But I like you,” she said to me.

I ignored her until she went away.

Eyes, eyes everywhere, empty sockets wreathed in shades of water, jungle, sun.

My raft heaved. I realized it had been boarded by a burly Norwegian sailor, shirtless, as shirtless as those people courting the madness of the waves, war paint blinding on their naked breasts, fucking, pleasure, salt on their lips beneath the moon.

Lars, he said. He told me of his time in the Navy. He told me he would guide me through. And he tells me that there are no spies, that there is water enough, and that the mountains are somewhere far away - not here, where the land meets the sea.

But there. In the shadow of the five treasures of the high snow.

They are looking out over the tea bushes rolling down, like waves in a manicured ocean of green.

I can see them perched high above, next to the wicker chairs and potted palms on the wrap-around verandah, leaning. Behind them, electric bulbs flicker inside the bungalow. A generator hums. Jazz bobs and weaves on a gramophone.

Samantha, three or four gins in. Edmund working another whisky.

“The tennis court,” he slurs.

“The tennis court,” she registers. “You don’t have to say anything.”

“Let’s not go there,” Lars cautions, his voice trapped in some dark and distant place.

“The Deputy Commissioner’s bungalow,” Edmund persists. “Us on one side. Japs on the other. The net line, no-man’s-land. We lobbed grenades across the court like tennis balls. The dead lay where they fell. I had a mean serve.” He chuckles darkly. Sways. “The sun was out, real bloody bright. This one kid, eighteen, nineteen maybe, he falls right onto my bayonet. I can smell the jungle on his breath, the loam. Blood, heat. He, uh… He keeps reaching, wanting something, I don’t know what until he’s gone, I didn’t know what. My sunglasses... The reflection, he didn’t want to watch himself die. But I was too late. Too late. He was the last thing he saw.”

“Come back,” Lars says. “There’s someone here for you.”

Kasia, hair electric in the wind, the tip of her nose spotted with neon paint. She looks like a cat. She often reminds me of a cat, though to her childhood friends in Eastern Europe, she is “gazela” - quick, delicate, wild. “Do you want to go to the water?”, she asks in music. I feel Lars pushing me to my feet and suddenly her hand in mine.

How many hours have passed?

Low tide. Ribbons of wet sand exhale beneath my feet, exposed by the moonlight.

She speaks, but I hear only the music, only the lilting rise and fall of her voice, the sound itself the meaning, the words empty containers breaking against the mushroomed reef of my mind. I feel her touch as a sensation far away.

“Dance with me,” she breathes. Her arms drape my neck and the thought rises, no, she can’t possibly mean me. I don’t know the steps. They burned the village because of me. Malaria killed the mother because of me, her brain swelled, her body suffocated from the inside because of my selfishness, because of me. I don’t know the steps and I can’t understand you. You can’t understand me, we are separated by a world of experience that burns any bridge between us.

“I can’t,” Edmund says.

“It’s just a simplified two-step,” Samantha says, trying to coax Edmund into a swing.

“If you mean to move like that, I need another drink in me.”

“I think you have plenty.”

“I’m cold,” I say, pulling out of Kasia’s embrace. Willowy, swimmer’s shoulders, pools for eyes. “I have to go.”

Back to my life raft, where it is safe, where no bridges can reach.

Edmund watches Samantha float through the bungalow haloed by the light. She gets her glass of water, meets Edmund’s glassy eyes and starts toward him - but a man intercepts. Indian, linen blazer, crisp cotton shirt. Collar open to the night.

Edmund watches them speak. Samantha laughs in her American way.

They sway, turning gently, falling into the two-step meant for him.

Where the land meets the sea, I resume my post beside Lars.

“She’s into you,” he says. “I’m jealous.”

“She’s out of my league,” I say.

“I said she’s into you.”

My eyes follow Kasia’s solitary stroll through Lanta’s low tide, silhouetted against the starry black. And then suddenly she is not alone. The shape of a man approaches.

For a long time, they speak. Then they continue down the beach together.

My heart pours into a vast emptiness.

“Why did he win?”, Lars asks me in a teacher’s tone. I feel his brotherly hand on my back.

“Because he was there,” I say.

“Because he was there,” Lars concludes. “Because he was available. She was fucking hunting, my friend.”

I look after them as they walk away from Mushroom Bar into the darkness, until there is nothing left to see.

It wasn’t the iceberg above the surface that sunk the Titanic. It was the one hundred thousand year-old behemoth beneath.

Assumptions crystallized by choices and their consequences, rippling through time.

I didn’t see Kasia again for many years.

And as Edmund left Samantha to dance with the man in the bungalow, he couldn’t have known that his decision, made in the blink of a single moment - fleeting, unornamented, a footnote - would alter the trajectory of his life.

➡️ Did you miss Part I (the introduction) to HOUSE OF SNOW?

If so, start here:

If you’re navigating a creative pivot and want a focused 1:1 conversation, I offer free storytelling consults. We talk projects, direction, & how to shape your next chapter.

Nice mix of fiction and autobiography. Who knew you were a novelist?? 😍

Loving your work!